As marine conservation races against a looming 2030 biodiversity target, one of the greatest frontiers—and challenges—lies in protecting the High Seas: the vast ocean areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ). Despite the size and importance of ABNJ, these waters – including the water column of the High Seas and the seabed (also known in legal terms as “the Area”) – remain largely unprotected and are governed by fragmented legal frameworks.

A new policy analysis by Henry et al. (2025) sheds invaluable light on how transformative processes can overcome entrenched obstacles to High Seas conservation and sustainable use. This study focuses on the scientific and policy journey of the North Atlantic Current and Evlanov Sea basin Marine Protected Area (NACES MPA), offering a practical blueprint for future efforts under the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement to identify the means by which area-based management tools can be established.

High Seas Protection: An Unfinished Project

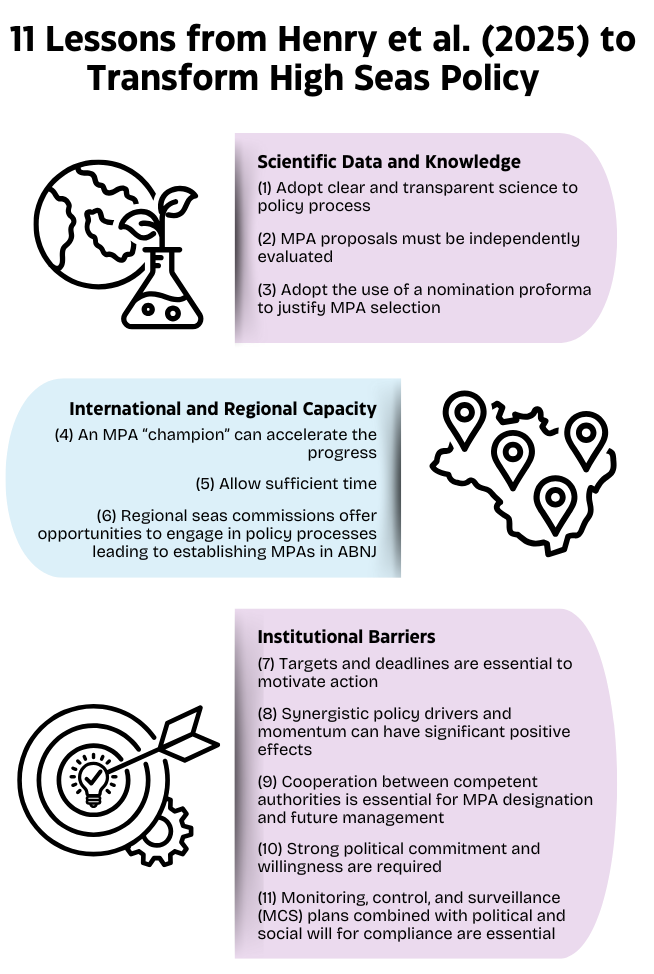

Progress on marine protected areas (MPAs) in ABNJ has long been hindered by three core challenges:

- Scientific Data Gaps – Historically, the High Seas were considered “data poor,” undermining evidence-based decision-making.

- Limited Regional Capacity – Many regions lack the institutions, expertise, or funding to shepherd complex policy processes across borders.

- Institutional Barriers – Fragmented governance and overlapping mandates create stagnation in policy action.

Henry et al. (2025)’s recent article in Marine Policy tackles these issues directly and investigates whether recent policy developments represent incremental tweaks or true transformation in High Seas governance.

NACES MPA: A Living Laboratory for Policy Innovation

Designated in 2021 under the OSPAR Convention and re-nominated in 2023, the NACES MPA covers nearly 600,000 km² in the North Atlantic. Initially established to protect key foraging areas for seabirds, it now includes broader goals for marine biodiversity conservation, extending fully down to the seafloor.

This re-nomination followed a two-year scientific process guided by a structured roadmap. A robust scientific evidence base was developed by integrating spatial data on geodiversity, benthic and pelagic ecosystems, species distributions, and physical oceanographic conditions. This was combined with insights from international workshops and extensive literature reviews. Together, these efforts provided the foundation for revising the MPA’s nomination proforma extending protections to explicitly include the seabed and subsoil, as well as measures aimed at safeguarding ecosystems, habitats, species, and essential ecological processes in addition to those already identified as protecting seabirds.

Henry et al. use NACES as a case study to apply a comparative framework built from eleven “lessons learned” in earlier ABNJ MPA processes. This analysis reveals clear evidence of transformative change, including:

- Data-Driven Policy: Contrary to the notion of the High Seas as data-deficient, the NACES process harnessed multidisciplinary science. Seabird tracking data involving over 2,000 individuals, high-resolution ocean circulation models, and AI-derived fishing effort data from Global Fishing Watch collectively informed the MPA boundaries and objectives.

- Transparent Processes: OSPAR’s use of a structured nomination proforma, iterative expert workshops, and open public consultations marked a significant advance in science-to-policy transparency.

- Independent Review and Rigour: The International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES) provided crucial independent evaluations of the scientific basis for the MPA, enhancing trust among stakeholders.

- Precautionary Principle in Action: Lacking perfect data for some deep-sea features, the revised NACES proposal used some analogues from similar ecosystems—a practical embodiment of the precautionary approach.

- Regional Cooperation: OSPAR’s Collective Arrangement with the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) proved critical for coordinating conservation measures without undermining other sectors’ mandates.

These innovations suggest that the NACES process goes beyond policy improvements for a particular MPA within its own network, but also offers an effective example for strengthening ABNJ conservation.

Technology as a Catalyst

One of Henry et al.’s key findings is the transformative role of technology. Artificial intelligence and big data analytics are rapidly changing how we perceive—and manage—the High Seas:

- Vessel Tracking: Global Fishing Watch uses automatic identification system (AIS) signals and machine learning to estimate apparent fishing effort, revealing spatial overlaps between human activities and ecologically sensitive zones.

- Ocean Modelling and Animal Tracking: Animal tagging studies, particle tracking and high-resolution circulation models unveiled the influence of mesoscale eddies in concentrating biodiversity hotspots and habitat use by marine megafauna—a pivotal insight for delineating MPA boundaries.

- Remote Sensing and Expeditions: New multibeam bathymetric data led to the discovery of previously unknown seafloor features like the “Mount Doom” seamount, highlighting the dynamic and often surprising nature of deep-sea ecosystems.

Such technological advances can help overcome one of the most persistent obstacles in High Seas conservation: the alleged scarcity of data.

Policy Lessons with Global Relevance

Henry et al. conclude that many lessons from NACES are interdependent. For instance, a clear science-to-policy process (Lesson 1) underpins stakeholder trust, while firm deadlines (Lesson 7) generate political momentum. Crucially, regional seas commissions like OSPAR emerge as essential facilitators of cooperation, especially in regions where overlapping sectoral mandates can otherwise stall conservation efforts.

However, significant challenges for High Seas conservation still remain, such as how:

- Climate Change threatens to reshape ocean ecosystems in ways that complicate static MPA boundaries.

- Capacity Gaps persist in regions lacking institutional support and coordinating bodies.

- Data Sharing and Transparency across sectors, particularly fisheries, remain imperfect, hindering integrated management.

As the BBNJ Agreement inches ever closer to entering into force, the policy innovations documented by Henry et al. and the recommendations for further efforts to increase the resilience of area-based management tools (ABMTs) in a changing ocean offer key insights for operationalising future ABNJ MPAs.

A Hopeful Path Forward

The NACES MPA story is more than a regional conservation success; it’s a test case for how science, diplomacy, and technology can converge to protect some of Earth’s most remote yet vital ecosystems.

Henry et al. (2025) remind us that while the High Seas remain complex and contested, transformative policy change is possible. Their analysis provides both a note of caution about the obstacles still ahead, but also a hopeful glimpse into how the world might meet the challenge of safeguarding the blue heart of our planet.

References

Henry, L.-A., Cleland, J., Gebruk, A., Emmerson, R., Hennicke, J., Davies, T., & Roberts, J. M. (2025). Navigating a transformative policy route for High Seas conservation. Marine Policy, 180, 106785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2025.106785